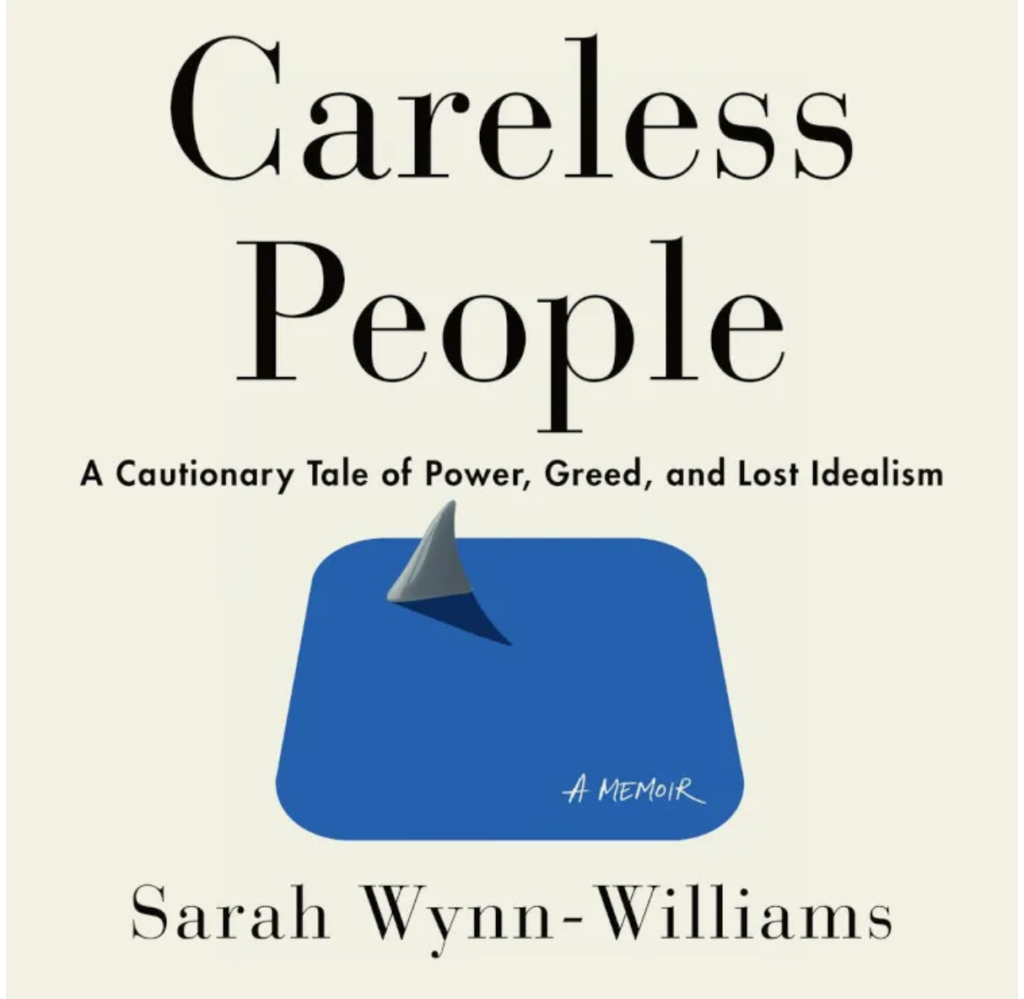

When I saw Sarah Wynn-Williams had published Careless People – an Expose on Facebook, my first thought was, I can relate. Working at Facebook in ads for in 2016, I was bullied, and harassed by toxic coworkers.

I got death threats on the phone.

All because I didn’t fit in to the clique.

Facebook encouraged employees to get their friends to come and work in the advertising department. As a result, it became one giant clique of people who had poor social skills, almost no emotional intelligence, and tended towards bullying.

This was a fucking job. Not a fraternity. Why was I being bullied, singled-out and treated like a second class citizen? Was this just initial hazing, and I’d be accepted eventually?

No.

It was because I didn’t get the job through a friend’s recommendation – but based on my own merits having already worked at Apple and Microsoft. After a year working in ads, I was let go, due to one woman’s decision that no one agreed with. Including my hiring manager, Zach. And other managers.

I’d trained new hires who shadowed me, wrote knowledge-base articles still used to this day for process flows like what do you do when an ex-employee still has control of your business’s Facebook Page but has left the company.

I’d made significant contributions that to this day still shape the learning of new hires with my contribution to the KB. Not only that, but I had sincerely dedicated myself to understanding social media, advertising, and marketing. I booked trips to business conferences on my own dime to learn more about product launches, social media marketing and the field I worked in.

In 2017, Facebook reached out and wanted me back. I got hired on at my second role at Facebook in tech, supporting Facebook’s servers and remote access tools, I thought things were getting better. Less drama than ads.

That was until a co-worker from my Facebook ad days named Brooke, a truly toxic individual, approached me as I sat at the tech desk, getting my Facebook Macbook serviced and demanded that I explain to her why I had deleted her as a friend on Facebook.

Now, at this point, if you looked at my block list on my personal Facebook profile, it contained literally the entire department of Facebook ad support in Austin, Texas. That is how bad these people were.

Bullies.

Socially toxic people without the ability to read the room. Who lacked all self awareness of their actions and the effect they had.

Back to Brooke. She is in my face, hostile, demanding I justify myself before her, on why I deleted her off of Facebook. Despite the fact that her very actions in that moment were exampling why I would delete such a toxic person from my social circle.

I tried to explain this to her. Well, little did I know, the tech guy was one of her friends. She made an HR complaint and threatened my new job in tech at Facebook.

I had to beg for forgiveness with HR, and write an apology letter for deleting Brooke off of Facebook to save my job. Because Brooke got the tech guy to side with her and testify against me.

This is how toxic it was at Facebook. Even in a role I thought would be free of the drama as tech jobs that are not customer facing tend to be safe from this type of bullshit. I guess that doesn’t count when the people you work with like to be dramatic and wield influence and connections like a club to beat you over the head with.

Fast forward a month or two later, I get word on the grapevine, the Facebook ad coworker who had stalked and harassed me with death threats on the phone was trying to join my small 6 person team that supported Facebook’s servers.

My manager wouldn’t take my word for it and not hire him. I had to start the process of filing a restraining order against him before she decided not to hire a man who stalks his coworkers outside of work.

Eventually she was overburdened by Facebook refusing to expand our tiny team of 6 people that were responsible for keeping Facebook.com online if too many ads were pending on the servers. We supported all of Facebook’s outsourced sweatshops in India when they had tech issues with their tools reviewing organic content.

I had to watch a woman in Morocco get beheaded on Facebook Live because the content moderator I was doing tech support for was having issues with his video scrubbing tools.

I had PTSD from some of the things I had to witness while working in that department. My manager, she was now being asked to do 8 jobs, without the staff to support her and was burnt out. She’d always had a crush on my coworker Ryan, it was public knowledge.

When she left, quit her job as the manager of our team, and moved on to a managerial position in tech, the supervisor role was open. I thought, given my prior experience as a manager at American Cancer Society, organizing Breast Cancer Awareness walks across the nation, doing quality assurance and employee training, I was a shoe in.

But, once again, Facebook prioritized who you know, not WHAT you know. Ryan’s last role was delivering pizza, yet, because of my manager’s crush on him, her influence got him to become manager.

I guess he never learned about the Feedback Sandwich approach to managing. Because his imposter syndrome knowing he was not qualified as me to be a manager, really kicked in. All I got was negative feedback, every day, for months. No acknowledgement of anything I’d done right.

Despite writing an entire technical training manual for our department, several internal wikipedia articles for more process flows in the KB, getting another role filled on the team with one of my prior coworkers in ads and much more.

It got to the point where I was having panic attacks at night, trying to go to sleep.

That will happen when you go to work everyday with a boss who is not qualified for his role, micromanaging, and making you the punching bag for all his insecurities.

So, I put in my 2 weeks notice, and left Facebook. I left on good terms, from an HR perspective..I didn’t tell anyone why I was really leaving: for better mental health.

Because Facebook prioritizes WHO you know not WHAT you know, it was a perfect example of Peter’s Principle.

And, who wants to go to a job where you are constantly at the whim of people with low emotional intelligence, and use their power to hurt rather than help? For the record, until Ryan became my manager, I really enjoyed the job. I got to work remote way before 2020 ever hit and had a hybrid schedule.

Fast forward to 2022, Facebook, now calling itself Meta, called me up and wanted me to return as a Project Manager. Now, I already had my own business at this point, as a policy consultant, but, given how much they were paying me and letting me work remote – I decided to give it a go.

It was a great job. My manager Abe, was an incredible human being, we’re still friends to this day. Ally, one of the upper tier managers there, gave off evil vibes and was one of the worst human beings I’ve ever interacted with.

In our little bubble, in New Products, it was safe. Our team was fairly healthy. I really enjoyed being a Project Manager. It was probably the least toxic position I was in. Mark Zuckerberg personally announced one of the projects I was in charge of.

So, on to Sarah Wynn-Williams’ Careless People. Sarah worked a lot higher up than me, even though my role as a PM, working directly with the engineers that wrote the code for Facebook was closer to royalty than my work in ads, where I was stalked, harassed and bullied constantly.

Even to this day, last year, Rex, a coworker I had in ads, continues to try to bully me online and leave comments on YouTube videos for interviews I’ve done about my work at Facebook. The level of bad mental health in the ads department is unparalleled. I’ve never been treated like that at any job I’ve worked.

I’d like to share a nice write up by Cory Doctorow on Careless People in case you didn’t have time to read it.

Careless People TLDR

1. Facebook’s Role in Global Harm and Genocide

-

Enabled the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar through inaction, poor moderation, and lack of Burmese language support.

-

Ignored repeated warnings from NGOs and human rights groups about the platform being used to incite ethnic violence.

-

Built surveillance and censorship tools for the Chinese government to spy on and control both Chinese and global Facebook users, despite never gaining official entry into China.

-

These tools were later used by China against Hong Kong, Taiwan, and independence movements.

2. Sexual Harassment and Toxic Leadership Culture

-

Joel Kaplan, VP of Global Policy and ex-boyfriend of Sheryl Sandberg, routinely sexually harassed Wynn-Williams and others.

-

Kaplan retaliated against Wynn-Williams with negative performance reviews while she was recovering from life-threatening childbirth complications.

-

Sandberg exhibited inappropriate behavior toward female staff, including asking Wynn-Williams to sleep beside her on private jets.

3. Zuckerberg’s Arrogance, Infantilism, and Negligence

-

Zuckerberg refuses to be briefed on important issues longer than a single text message.

-

Frequently derails key initiatives through impulsive, unplanned statements (e.g., promising internet for refugees without any plan).

-

Demands subordinates let him win at board games; lashes out when they don’t (accuses Wynn-Williams of cheating).

-

Embarked on a desperate, humiliating campaign to court China (learning Mandarin, studying Xi Jinping’s book, asking Xi to name his child), which ultimately failed.

4. Sheryl Sandberg’s Ruthlessness and Self-Interest

-

Prioritized self-promotion, particularly her “Lean In” brand, over Facebook’s global diplomacy efforts.

-

Made morally repugnant comments, such as advocating the right to purchase a kidney from Mexico if needed for her child.

5. Global Expansion Driven by Stock Volatility and Growth Addiction

-

Facebook’s rapid global expansion was less about connecting people and more about maintaining its growth stock valuation.

-

Growth pressures were tied to the need to keep share prices high so they could issue stock instead of spending cash on acquisitions (like WhatsApp and Instagram).

-

When U.S. user growth slowed, Facebook aggressively pivoted to international markets out of financial necessity.

6. Monopoly Power and Strategic Capture of Competitors, Regulators, and Employees

-

Acquired Instagram and WhatsApp to prevent competition and user defection.

-

Captured regulators and politicians by becoming critical to political campaigns (e.g., Obama) and selling political ads globally.

-

Cultivated fear and compliance among employees, especially engineers, by monopolizing top talent pipelines and limiting labor pushback.

7. Facebook’s Business Model Profits from Dictators, Autocrats, and Hate Speech

-

Pivoted Facebook’s global policy shop from government relations to political ad sales, often empowering dictators and autocrats.

-

Made political disinformation, disenfranchisement, and ethnic violence a revenue stream.

8. Systemic Dishonesty and Routine Deception

-

Lied to the public, courts, UN, Congress, and advertisers about platform capabilities and harm.

-

Allowed advertisers to target depressed teens who felt “worthless” while falsely denying knowledge of such practices.

-

Overstated targeting reach and efficacy to advertisers, including offering ad inventory for more teens than actually existed.

9. Internal Dissent and the Rise of Secret Resistance Networks

-

Wynn-Williams and others formed private Facebook groups to track internal failures on Myanmar moderation and sexual harassment cases.

-

Employees resorted to these clandestine spaces because official channels were dismissive or hostile to whistleblowing.

10. The Decline from Reckless to Remorseless (“Too Big to Care”)

-

Facebook evolved from being reckless due to arrogance to being remorseless due to impunity.

-

Shifted from fearing consequences to knowing they could avoid them through:

-

Market dominance (too big to fail)

-

Regulatory capture (too big to jail)

-

Lack of employee power (too big to care)

-

11. Policy Failure as the Real Villain

-

The book argues that these abuses were not just personal failings but systemic outcomes of weak antitrust enforcement, ineffective privacy laws, and corporate-friendly policies.

-

The true accountability lies in policy choices that allowed Facebook’s monopoly power and disregard for human harm to flourish.

12. Current Global Regulatory Backlash

-

Meta now faces antitrust action in the U.S. and strict enforcement of digital rules in the EU.

-

There is a growing global consensus on the need to regulate Big Tech more aggressively to prevent further abuse.

OK Now that you’ve read the TLDR, here’s Doctorow’s full write up of Careless People:

Cory Doctorow’s Analysis of Careless People & Summary

I never would have read Careless People, Sarah Wynn-Williams’s tell-all memoir about her years running global policy for Facebook, but then Meta’s lawyer tried to get the book suppressed and secured an injunction to prevent her from promoting it:

So I’ve got something to thank Meta’s lawyers for, because it’s a great book! Not only is Wynn-Williams a skilled and lively writer who spills some of Facebook’s most shameful secrets, but she’s also a kick-ass narrator (I listened to the audiobook, which she voices):

https://libro.fm/audiobooks/9781250403155-careless-people

I went into Careless People with strong expectations about the kind of disgusting behavior it would chronicle. I have several friends who took senior jobs at Facebook, thinking they could make a difference (three of them actually appear in Wynn-Williams’s memoir), and I’ve got a good sense of what a nightmare it is for a company.

But Wynn-Williams was a lot closer to three of the key personalities in Facebook’s upper echelon than anyone in my orbit: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Joel Kaplan, who was elevated to VP of Global Policy after the Trump II election. I already harbor an atavistic loathing of these three based on their public statements and conduct, but the events Wynn-Williams reveals from their private lives make these three out to be beyond despicable. There’s Zuck, whose underlings let him win at board-games like Settlers of Catan because he’s a manbaby who can’t lose (and who accuses Wynn-Williams of cheating when she fails to throw a game of Ticket to Ride while they’re flying in his private jet). There’s Sandberg, who demands the right to buy a kidney for her child from someone in Mexico, should that child ever need a kidney.

Then there’s Kaplan, who is such an extraordinarily stupid and awful oaf that it’s hard to pick out just one example, but I’ll try. At one point, Wynn-Williams gets Zuck a chance to address the UN General Assembly. As is his wont, Zuck refuses to be briefed before he takes the dais (he’s repeatedly described as unwilling to consider any briefing note longer than a single text message). When he gets to the mic, he spontaneously promises that Facebook will provide internet access to refugees all over the world. Various teams at Facebook then race around, trying to figure out whether this is something the company is actually doing, and once they realize Zuck was just bullshitting, set about trying to figure out how to do it. They get some way down this path when Kaplan intervenes to insist that giving away free internet to refugees is a bad idea, and that instead, they should sellinternet access to refugees. Facebookers dutifully throw themselves into this absurd project, which dies when Kaplan fires off an email stating that he’s just realized that refugees don’t have any money. The project dies.

The path that brought Wynn-Williams into the company of these careless people is a weird – and rather charming – one. As a young woman, Wynn-Williams was a minor functionary in the New Zealand diplomatic corps, and during her foreign service, she grew obsessed with the global political and social potential of Facebook. She threw herself into the project of getting hired to work on Facebook’s global team, working on strategy for liaising with governments around the world. The biggest impediment to landing this job is that it doesn’t exist: sure, FB was lobbying the US government, but it was monumentally disinterested in the rest of the world in general, and the governments of the world in particular.

But Wynn-Williams persists, pestering potentially relevant execs with requests, working friends-of-friends (Facebook itself is extraordinarily useful for this), and refusing to give up. Then comes the Christchurch earthquake. Wynn-Williams is in the US, about to board a flight, when her sister, a news presenter, calls her while trapped inside a collapsed building (the sister hadn’t been able to get a call through to anyone in NZ). Wynn-Williams spends the flight wondering if her sister is dead or alive, and only learns that her sister is OK through a post on Facebook.

The role Facebook played in the Christchurch quake transforms Wynn-Williams’s passion for Facebook into something like religious zealotry. She throws herself into the project of landing the job, and she does, and after some funny culture-clashes arising from her Kiwi heritage and her public service background, she settles in at Facebook.

Her early years there are sometimes comical, sometimes scary, and are characteristic of a company that is growing quickly and unevenly. She’s dispatched to Myanmar amidst a nationwide block of Facebook ordered by the ruling military junta and at one point, it seems like she’s about to get kidnapped and imprisoned by goons from the communications ministry. She arranges for a state visit by NZ Prime Minister John Key, who wants a photo-op with Zuckerberg, who – oblivious to the prime minister standing right there in front of him – berates Wynn-Williams for demanding that he meet with some jackass politician (they do the photo-op anyway).

One thing is clear: Facebook doesn’t really care about countries other than America. Though Wynn-Williams chalks this up to plain old provincial chauvinism (which FB’s top eschelon possess in copious quantities), there’s something else at work. The USA is the only country in the world that a) is rich, b) is populous, and c) has no meaningful privacy protections. If you make money selling access to dossiers on rich people to advertisers, America is the most important market in the world.

But then Facebook conquers America. Not only does FB saturate the US market, it uses its free cash-flow and high share price to acquire potential rivals, like Whatsapp and Instagram, ensuring that American users who leave Facebook (the service) remain trapped by Facebook (the company).

At this point, Facebook – Zuckerberg – turns towards the rest of the world. Suddenly, acquiring non-US users becomes a matter of urgency, and overnight Wynn-Williams is transformed from the sole weirdo talking about global markets to the key asset in pursuit off the company’s top priority.

Wynn-Williams’s explanation for this shift lies in Zuckerberg’s personality, his need to constantly dominate (which is also why his subordinates have learned to let him win at board games). This is doubtless true: not only has this aspect of Zuckerberg’s personality been on display in public for decades, Wynn-Williams was able to observe it first-hand, behind closed doors.

But I think that in addition to this personality defect, there’s a material pressure for Facebook to grow that Wynn-Williams doesn’t mention. Companies that grow get extremely high price-to-earnings (P:E) ratios, meaning that investors are willing to spend many dollars on shares for every dollar the company takes in. Two similar companies with similar earnings can have vastly different valuations (the value of all the stock the company has ever issued), depending on whether one of them is still growing.

High P:E ratios reflect a bet on the part of investors that the company will continue to grow, and those bets only become more extravagant the more the company grows. This is a hugeadvantage to companies with “growth stocks.” If your shares constantly increase in value, they are highly liquid – that is, you can always find someone who’s willing to buy your shares from you for cash, which means that you can treat shares like cash. But growth stocks are better than cash, because money grows slowly, if at all (especially in periods of extremely low interest rates, like the past 15+ years). Growth stocks, on the other hand, grow.

Best of all, companies with growth stocks have no trouble finding more stock when they need it. They just type zeroes into a spreadsheet and more shares appear. Contrast this with money. Facebook may take in a lot of money, but the money only arrives when someone else spends it. Facebook’s access to money is limited by exogenous factors – your willingness to send your money to Facebook. Facebook’s access to shares is only limited by endogenous factors – the company’s own willingness to issue new stock.

That means that when Facebook needs to buy something, there’s a very good chance that the seller will accept Facebook’s stock in lieu of US dollars. Whether Facebook is hiring a new employee or buying a company, it can outbid rivals who only have dollars to spend, because that bidder has to ask someone else for more dollars, whereas Facebook can make its own stock on demand. This is a massive competitive advantage.

But it is also a massive business risk. As Stein’s Law has it, “anything that can’t go on forever eventually stops.” Facebook can’t grow forever by signing up new users. Eventually, everyone who might conceivably have a Facebook account will get one. When that happens, Facebook will need to find some other way to make money. They could enshittify – that is, shift value from the company’s users and customers to itself. They could invent something new (like metaverse, or AI). But if they can’t make those things work, then the company’s growth will have ended, and it will instantaneously become grossly overvalued. Its P:E ratio will have to shift from the high value enjoyed by growth stocks to the low value endured by “mature” companies.

When that happens, anyone who is slow to sell will lose a tonof money. So investors in growth stocks tend to keep one fist poised over the “sell” button and sleep with one eye open, watching for any hint that growth is slowing. It’s not just that growth gives FB the power to outcompete rivals – it’s also the case that growth makes the company vulnerable to massive, sudden devaluations. What’s more, if these devaluations are persistent and/or frequent enough, the key FB employees who accepted stock in lieu of cash for some or all of their compensation will either demand lots more cash, or jump ship for a growing rival. These are the very same people that Facebook needs to pull itself out of its nosedives. For a growth stock, even small reductions in growth metrics (or worse, declines) can trigger cascades of compounding, mutually reinforcing collapse.

This is what happened in early 2022, when Meta posted slightly lower-than-anticipated US growth numbers, and the market all pounded on the “sell” button at once, lopping $250,000,000,000 of the company’s valuation in 24 hours. At the time, it was the worst-ever single day losses for any company in human history:

Facebook’s conquest of the US market triggered an emphasis on foreign customers, but not just because Zuck is obsessed with conquest. For Facebook, a decline in US growth posed an existential risk, the possibility of mass stock selloffs and with them, the end of the years in which Facebook could acquire key corporate rivals and executives with “money” it could print on the premises, on demand.

So Facebook cast its eye upon the world, and Wynn-Williams’s long insistence that the company should be paying attention to the political situation abroad suddenly starts landing with her bosses. But those bosses – Zuck, Sandberg, Kaplan and others – are “careless.” Zuck screws up opportunity after opportunity because he refuses to be briefed, forgets what little information he’s been given, and blows key meetings because he refuses to get out of bed before noon. Sandberg’s visits to Davos are undermined by her relentless need to promote herself, her “Lean In” brand, and her petty gamesmanship. Kaplan is the living embodiment of Green Day’s “American Idiot” and can barely fathom that foreigners exist.

Wynn-Williams’s adventures during this period are very well told, and are, by turns, harrowing and hilarious. Time and again, Facebook’s top brass snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, squandering incredible opportunities that Wynn-Williams secures for them because of their pettiness, short-sightedness, and arrogance (that is, their carelessness).

But Wynn-Williams’s disillusionment with Facebook isn’t rooted in these frustrations. Rather, she is both personally and professionally aghast at the company’s disgusting, callous and cruel behavior. She describes how her boss, Joel Kaplan, relentlessly sexually harasses her, and everyone in a position to make this stop tells her to shut up and take it. When Wynn-Williams give birth to her second child, she hemorrhages, almost dies, and ends up in a coma. Afterwards, Kaplan gives her a negative performance review because she was “unresponsive” to his emails and texts while she was dying in an ICU. This is a significant escalation of the earlier behavior she describes, like pestering her with personal questions about breastfeeding, video-calling her from bed, and so on (Kaplan is Sandberg’s ex-boyfriend, and Wynn-Williams describes another creepy event where Sandberg pressures her to sleep next to her in the bedroom on one of Facebook’s jets, something Wynn-Williams says she routinely does with the young women who report to her).

Meanwhile, Zuck is relentlessly pursuing Facebook’s largest conceivable growth market: China. The only problem: China doesn’t want Facebook. Zuck repeatedly tries to engineer meetings with Xi Jinping so he can plead his case in person. Xi is monumentally hostile to this idea. Zuck learns Mandarin. He studies Xi’s book, conspicuously displays a copy of it on his desk. Eventually, he manages to sit next to Xi at a dinner where he begs Xi to name his next child. Xi turns him down.

After years of persistent nagging, lobbying, and groveling, Facebook’s China execs start to make progress with a state apparatchik who dangles the possibility of Facebook entering China. Facebook promises this factotum the world – all the surveillance and censorship the Chinese state wants and more. Then, Facebook’s contact in China is jailed for corruption, and they have to start over.

At this point, Kaplan has punished Wynn-Williams – she blames it on her attempts to get others to force him to stop his sexual harassment – and cut her responsibilities in half. He tries to maneuver her into taking over the China operation, something he knows she absolutely disapproves of and has refused to work on – but she refuses. Instead, she is put in charge of hiring the new chief of China operations, giving her access to a voluminous paper-trail detailing the company’s dealings with the Chinese government.

According to Wynn-Williams, Facebook actually built an extensive censorship and surveillance system for the Chinese state – spies, cops and military – to use against Chinese Facebook users, and FB users globally. They promise to set up caches of global FB content in China that the Chinese state can use to monitor all Facebook activity, everywhere, with the implication that they’ll be able to spy on private communications, and censor content for non-Chinese users.

Despite all of this, Facebook is never given access to China. However, the Chinese state is able to use the tools Facebook built for it to attack independence movements, the free press and dissident uprisings in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Meanwhile, in Myanmar, a genocide is brewing. NGOs and human rights activists keep reaching out to Facebook to get them to pay attention to the widespread use of the platform to whip up hatred against the country’s Muslim minority group, the Rohinga. Despite having expended tremendous amounts of energy to roll out “Free Basics” in Myanmar (a program whereby Facebook bribes carriers to exclude its own services from data caps), with the result that in Myanmar, “the internet” is synonymous with “Facebook,” the company has not expended anyeffort to manage its Burmese presence. The entire moderation staff consists of one (later two) Burmese speakers who are based in Dublin and do not work local hours (later, these two are revealed as likely stooges for the Myanmar military junta, who are behind the genocide plans).

The company has also failed to invest in Burmese language support for its systems – posts written in Burmese script are not stored as Unicode, meaning that none of the company’s automated moderation systems can parse it. The company is so hostile to pleas to upgrade these systems that Wynn-Williams and some colleagues create secret, private Facebook groups where they can track the failures of the company and the rising tide of lethal violence in the country (this isn’t the only secret dissident Facebook group that Wynn-Williams joins – she’s also part of a group of women who have been sexually harassed by colleagues and bosses).

The genocide that follows is horrific beyond measure. And, as with the Trump election, the company’s initial posture is that they couldn’t possibly have played a significant role in a real-world event that shocked and horrified its rank-and-file employees.

The company, in other words, is “careless.” Warned of imminent harms to its users, to democracy, to its own employees, the top executives simply do not care. They ignore the warnings and the consequences, or pay lip service to them. They don’t care.

Take Kaplan: after figuring out that the company can’t curry favor with the world’s governments by selling drone-delivered wifi to refugees (the drones don’t fly and the refugees are broke), he hits on another strategy. He remakes “government relations” as a sales office, selling political ads to politicians who are seeking to win over voters, or, in the case of autocracies, disenfranchised hostage-citizens. This is hugely successful, both as a system for securing government cooperation and as a way to transform Facebook’s global policy shop from a cost-center to a profit-center.

But of course, it has a price. Kaplan’s best customers are dictators and would-be dictators, formenters of hatred and genocide, authoritarians seeking opportunities to purge their opponents, through exile and/or murder.

Wynn-Williams makes a very good case that Facebook is run by awful people who are also very careless – in the sense of being reckless, incurious, indifferent.

But there’s another meaning to “careless” that lurks just below the surface of this excellent memoir: “careless” in the sense of “arrogant” – in the sense of not caring about the consequences of their actions.

To me, this was the most important – but least-developed – lesson of Careless People. When Wynn-Williams lands at Facebook, she finds herself surrounded by oafs and sociopaths, cartoonishly selfish and shitty people, who, nevertheless, have built a service that she loves and values, along with hundreds of millions of other people.

She’s not wrong to be excited about Facebook, or its potential. The company may be run by careless people, but they are still prudent, behaving as though the consequences of screwing up matter. They are “careless” in the sense of “being reckless,” but they care, in the sense of having a healthy fear (and thus respect) for what might happen if they fully yield to their reckless impulses.

Wynn-Williams’s firsthand account of the next decade is not a story of these people becoming more reckless, rather, it’s a story in which the possibility of consequences for that recklessness recedes, and with it, so does their care over those consequences.

Facebook buys its competitors, freeing it from market consequences for its bad acts. By buying the places where disaffected Facebook users are seeking refuge – Instagram and Whatsapp – Facebook is able to insulate itself from the discipline of competition – the fear that doing things that are adverse to its users will cause them to flee.

Facebook captures its regulators, freeing it from regulatory consequences for its bad acts. By playing a central role in the electoral campaigns of Obama and then other politicians around the world, Facebook transforms its watchdogs into supplicants who are more apt to beg it for favors than hold it to account.

Facebook tames its employees, freeing it from labor consequences for its bad acts. As engineering supply catches up with demand, Facebook’s leadership come to realize that they don’t have to worry about workforce uprisings, whether incited by impunity for sexually abusive bosses, or by the company’s complicity in genocide and autocratic oppression.

First, Facebook becomes too big to fail.

Then, Facebook becomes too big to jail.

Finally, Facebook becomes too big to care.

This is the “carelessness” that ultimately changes Facebook for the worse, that turns it into the hellscape that Wynn-Williams is eventually fired from after she speaks out once too often. Facebook bosses aren’t just “careless” because they refuse to read a briefing note that’s longer than a tweet. They’re “careless” in the sense that they arrive at a juncture where they don’t have to care who they harm, whom they enrage, who they ruin.

There’s a telling anecdote near the end of Careless People. Back in 2017, leaks revealed that Facebook’s sales-reps were promising advertisers the ability to market to teens who felt depressed and “worthless”:

Wynn-Williams is – rightly – aghast about this, and even more aghast when she sees the company’s official response, in which they disclaim any knowledge that this capability was being developed and fire a random, low-level scapegoat. Wynn-Williams knows they’re lying. She knows that this is a routine offering, one that the company routinely boasts about to advertisers.

But she doesn’t mention the other lies that Facebook tells in this moment: for one thing, the company offers advertisers the power to target more teens than actually exist. The company proclaims the efficacy of its “sentiment analysis” tool that knows how to tell if teens are feeling depressed or “worthless,” even though these tools are notoriously inaccurate, hardly better than a coin-toss, a kind of digital phrenology.

Facebook, in other words, isn’t just lying to the public about what it offers to advertisers – it’s lying to advertisers, too. Contra those who say, “if you’re not paying for the product, you’re the product,” Facebook treats anyone it can get away with abusing as “the product” (just like every other tech monopolist):

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

Wynn-Williams documents so many instances in which Facebook’s top executives lie – to the courts, to Congress, to the UN, to the press. Facebook lies when it is beneficial to do so – but only when they can get away with it. By the time Facebook was lying to advertisers about its depressed teen targeting tools, it was already colluding with Google to rig the ad market with an illegal tool called “Jedi Blue”:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jedi_Blue

Facebook’s story is the story of a company that set out to become too big to care, and achieved that goal. The company’s abuses track precisely with its market dominance. It enshittified things for users once it had the users locked in. It screwed advertisers once it captured their market. It did the media-industry-destroying “pivot to video” fraud once it captured the media:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pivot_to_video

The important thing about Facebook’s carelessness is that it wasn’t the result of the many grave personality defects in Facebook’s top executives – it was the result of policy choices. Government decisions not to enforce antitrust law, to allow privacy law to wither on the vine, to expand IP law to give Facebook a weapon to shut down interoperable rivals – these all created the enshittogenic environment that allowed the careless people who run Facebook to stop caring.

The corollary: if we change the policy environment, we can make these careless people – and their successors, who run other businesses we rely upon – care. They may never care about us, but we can make them care about what we might do to them if they give in to their carelessness.

Meta is in global regulatory crosshairs, facing antitrust action in the USA:

And muscular enforcement pledges in the EU:

As Martin Luther King, Jr put it:

The law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.